Statement of Probable Cause That Carter-Oberstone Violated the Brown Act by Leaking a Confidential Investigation

And how Mayor Breed can initiate the removal process on him

Follow me on Twitter here.

Applicable Statute:

California Government Code section 54963(a)

A person may not disclose confidential information that has been acquired by being present in a closed session to a person not entitled to receive it.

Leaking confidential information is a misdemeanor criminal offense under the Brown Act

Of issue is Michael Barba’s article in the San Francisco Standard, Are San Francisco Police Officers Misreporting the Races of People They Stop? Accused of inaccurately recording the perceived race of people in his traffic stops, Officer Christopher Kosta’s name was somehow obtained by Barba from the confidential files either in the possession of the Department of Police Accountability (DPA) or the SF Police Commission. Barba claims he took independent steps to uncover Kosta, which as I will detail, were impossible to achieve and an apparent ruse to protect the criminal acts of his source/leaker.

In 2019, under Chief Scott, journalist Brian Carmondy received $369,000 in damages from San Francisco after his home was illegally searched by SFPD to ascertain which SFPD police officer accelerated (“leaked’) the release of Jeff Adachi’s public death certificate. If Chief Scott really supports the men and women of his department, he will apply the same zeal to legally investigate and find the leaker of Kosta’s confidential information.

I do not have access to the complete information on Kosta’s traffic stops, so I cannot weigh in on the merits of the investigation on him or his innocence. However, Judge Chan’s interpretation of Kosta’s recent court testimony, detailed in another Barba article, does raise my concerns.

Of greater importance than the accuracy or inaccuracy of Kosta’s recorded traffic data, is the apparent illegal release of confidential information on Kosta to Barba, which constitutes a misdemeanor criminal violation of the Brown Act.

The investigative trail Barba claims he took, to hide his source, appears fabricated

In Barba’s article, he went overboard to explain each step of how he unsealed Kosta’s name. His dance was just a little too big, and raised my antenna that he was trying to distract from his source’s criminal leak. Thus, in his article, he threw as many (alleged) investigative steps as possible against the wall, hoping some would stick. I retraced all of Barba’s steps and it appears it was the leaker that spoon-fed him the investigative route he could claim, because as you will read below, Barba’s alleged steps could not have led to his uncovering Kosta’s identity.

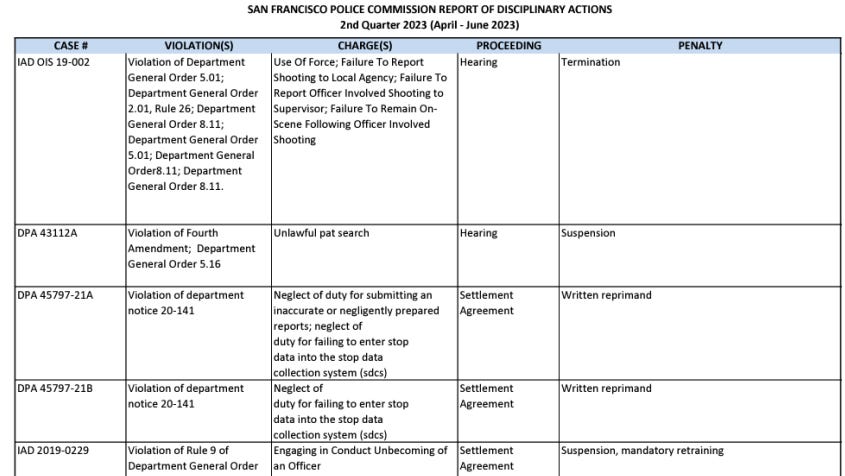

Step 1: In his article, Barba’s stated: “A June 2022 report by the Department of Police Accountability summarizing the complaints received by the agency includes a case number for the investigation.” I found the June 2022 summary with dozens of citizens’ complaints that Barba described (only a subset of those appears below). The problem with Barba’s story is that Kosta’s name was not disclosed in the June 2022 report, nor is the recording of an improper race listed as the violation. So, how was Barba able to identify the DPA case number against Kosta?

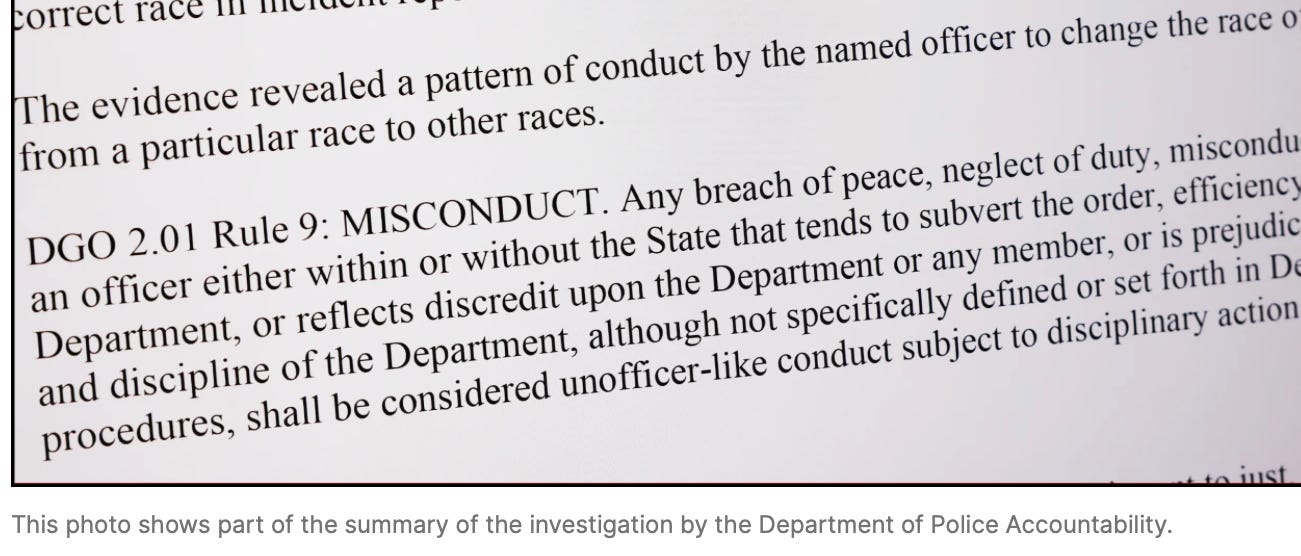

Step 2: Barba’s article also included an actual photograph of an excerpt from the “Investigative Summary” on Kosta (photograph below) that he was able to acquire by referencing the case number from Step 1.

I made a public records request to DPA asking for the full document Barba published (above). Interestingly, the anonymized document DPA sent me did not include Kosta’s name or a case number. Without someone leaking Kosta’s name or a case number included in this document, how was Barba able to acquire this report?

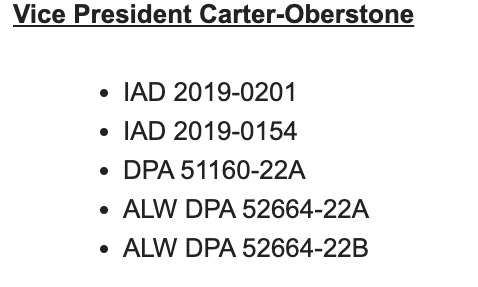

Step 3: As my suspicions grew, my next step was a public records request to the SF Police Commission asking for the disciplinary case numbers that had been assigned to each police commissioner. I then traced every commissioner’s assigned case numbers back to the June 2022 incoming complaints in Step 1 (above). Only one case was reconcilable, DPA 51160-22A, which was assigned to Carter-Oberstone (see Police Commission’s response below).

Despite the Kosta case being assigned to him for over 3 months, ironically at the September 21, 2023 Police Commission meeting, Carter-Oberstone said he was shocked, shocked, shocked to learn about the Kosta case from the Standard. (20 second video of MCO’s shock here.)

Step 4: In his article, Barba said, “A public summary of the (DPA’s) agency’s records requests to SFPD, in turn, repeatedly describes requests for information related to that case number as seeking data on stops by Kosta.” I made the exact same request to the DPA and got this response, which shows a few separate maters not involving Kosta (below).

First, in the document above, there was no evidence of DPA’s “repeated requests” for information to SFPD on Kosta as Barba describes. (Perhaps it was really Carter-Oberstone who made the requests, and there is no public records trail because police commissioners’ requests for information are not public or tracked?) Second, none of the case numbers from the document (above) reconcile to case number DPA 51160-22A that Barba found in Step 1 (above) and is in Commissioner Carter-Oberstone’s investigation inbox. It looks like this Step 4 was a phantom step to mislead readers.

Step 5: After the Police Commission meeting on the evening of September 13, 2023, Barba wrote the following passage in a subsequent story on SFPD’s traffic stops.

“A data analysis by The Standard separately found that more officers may be inaccurately reporting race data than the one facing discipline. One sergeant, for example, reported that all but six of the 1,139 people he stopped during a roughly three-year period ending in 2021 were white.”

Based on Barba’s second article, on September 19, 2023, I issued another public records request to DPA, and they responded:

The SFPD public records portal indicates Barba has made no recent public records requests to them. Nevertheless, predicated upon DPA’s response that they did not provide the San Francisco Standard with any data; I tendered a public request to SFPD asking for the data Barba might have accessed.

On September 21, 2023, SFPD provided me with large spreadsheets containing hundreds of thousands of SFPD’s traffic stops.[1] But…….the spreadsheets do not include SFPD officers names, star numbers, or other identifiers for references. Again, how could Barba pinpoint the SFPD sergeant’s traffic stop data in his article from these raw spreadsheets?

This means, that in the background it appears Carter-Oberstone and/or DPA are conducting greater analysis of the spreadsheets’ raw data and feeding the analysis to Barba. And if the accuracy of Carter-Oberstone’s and/or the DPA’s analysis that he publishes is not independently verified, then Barba is effectively giving free rein to them to cherrypick data and to skew the narrative based on their biases.[2]

The bottom line is that there is no way Barba could have uncovered the confidential information on Kosta without an illegal leak, and his alleged steps were a smokescreen to protect his source. I respect the fact that Barba cannot and should not reveal his source, but the evidence is overwhelming as to who his source is.

Why I believe Commissioner Carter-Oberstone’s fingerprints are all over the illegally leaked confidential information

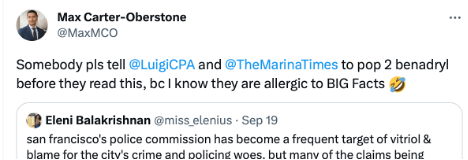

1) Carter-Oberstone’s modus operandi is to immediately repost on Twitter the media stories where he is most likely the source of the leak

Like an arsonist returning to admire the fire he created, whenever Carter-Oberstone is the unnamed, but obvious, source for a Chronicle or a Mission Local article; he immediately reposts the story on Twitter:

a) On January 24, 2023, when Carter-Oberstone was the likely source of the Chronicle’s Susie Neilson’s “frequently used words” article, Carter-Oberstone retweeted it:[3]

b) Last week when he was the obvious source for a Mission Local article defending the Police Commission, he immediately retweeted the article:

c) And, with Kosta’s confidential file sitting on his lap, Carter-Oberstone immediately retweeted Barba’s article as soon as it hit Twitter:

The significance of this last Carter-Oberstone tweet is of much greater significance than the first two reposts. As a public official Carter-Oberstone was assigned a confidential investigation and by retweeting the article, he was publicly approving Barba’s perspective. Unlike my probable cause allegations in the first part of this article, here we have definitive documentable evidence that Carter-Oberstone communicated his opinion on the Kosta case directly to the public- a second and easier proved criminal violation of the Brown Act.

At a minimum, Carter-Oberstone’s public approval of Barba’s story signals he has forfeited his objectivity and that he must recuse himself from further investigation or adjudicating on Kosta’s case.

Assignment of Kosta’s case to Carter-Oberstone and coincidental release of confidential information

On September 18, 2023, the San Francisco Police Commission responded to my public records request for the dates every investigative case was assigned to police commissioners. The Kosta case was assigned to Carter-Oberstone on July 12, 2023. Only after the case was assigned to Carter-Oberstone, was the illegal confidential information released to Barba.

2) The motivation and orchestrated timing of Barba’s article on the day of Police Commission hearing

Barba’s article was suspiciously published on September 13, 2023, the same day as the Police Commission meeting so that it could be a topic of discussion. Barba immediately released a supplemental article on the same subject after the Police Commission meeting.

At the meeting:

a) DPA’s Executive Director Paul Henderson said there was no way he could comment on Barba’s article, but Carter-Oberstone appeared to already know about a larger behind-the-scenes investigation. (Watch 20 seconds of their facial reactions.) By all appearances, the leaking of Kosta’s information was subterfuge for Henderson and Carter-Oberstone to ask for an independent agency or academia to audit SFPD’s traffic stops. (Think: Berkeley’s progressive Goldman School of Social Policy or Berkeley’s Chesa Boudin.)

b) Incredulously, at the commission meeting, Carter-Oberstone stated he “perused” a 400+ page Department of Justice 2016 report on reforming SFPD on his way to the commission meeting. He then cited and quoted from pages 356 and 357, feigning that he has a photographic memory. (Video here) Obviously, Carter-Oberstone knew the article was coming out and he brushed up on pages 356 and 357 long beforehand.[4]

It is transparent that Carter-Oberstone’s release of confidential information was part of a choreographed collaborated scheme with DPA to use Kosta’s traffic stops as justification for more scrutiny and regulations on SFPD, as it became a topic of discussion at the following Police Commission meeting (9/21/23) as well.

Legal justification for Mayor Breed to fire Max Carter-Oberstone

The San Francisco Charter, Section 4.109 Police Commission, fiats that the mayor is allowed to appoint four police commissioners. One of her appointees must be “either a retired judge or an attorney with trial experience.” Implied by this section, because the Police Commission deals with criminal matters, is that the appointee must have jury trial experiences in a “criminal court.” The generally accepted standard for “experience” in the legal community is “participating in a trial until a verdict is reached.” Not just sticking your head in the courtroom.

On Twitter, I have previously asked Carter-Oberstone to cite if he has participated in a single criminal jury trial experience, but he has ducked answering. Mayor Breed must force Carter-Oberstone to provide to the public, the case number of the trial where he was the counsel of record that meets the “attorney with trial experience” criteria. Or the mayor must replace him with someone that has the qualified experience, so that she is not out of compliance with the city charter.

The facts are that Max Carter-Oberstone is not professionally or ethically qualified to serve on the San Francisco Police Commission.

[1] Coincidentally, the Chronicle’s Susie Neilson wrote an article (1/24/23) on SFPD using the words as, at, from, with, and we more frequently on people of color. A riveting story. Per my public records request back in January 2023, SFPD responded that neither the Chronicle nor Neilson had requested traffic stop data. The spreadsheets SFPD provided me contained the same raw data that I received on the Kosta matter.

Enter Carter-Oberstone on a February 27, 2023 tweet, to defend Neilson.

Like the Kosta case, the tweet (above) was an admission by Carter-Oberstone that a) he had access to the database, and b) that because of his status as a commissioner, he could obtain the database outside the traceable public records request process. Mystery solved.

Seven months ago, Neilson emailed me that she would shortly provide me with a link to the data supporting her article. I’m still waiting.

[2] Susie Neilson article. In this article presumably handed to Neilson by Carter-Oberstone, my analysis found numerous “frequently used words” that were omitted and would have changed the narrative, but Neilson never fact checked Carter-Oberstone’s work.

[3] Ibid

[4] Does Carter-Oberstone really think we believe he read a 400+ page report while driving his car? By the way, this is an admission of a violation of California Vehicle Code section 23125.5-- by a police commissioner. Or would a traffic stop for this have been considered a pretext stop?

That is some serious investigative work. Well done. Oberstone needs to exit left.

The commission plays dirty….who then oversees the overseers?